This article refers to the absence of a 'dance culture' among men in some Western cultures, as well as to men's lack of 'resonance' with what might be called 'romantic dance'. It aims to throw some light on why men are not inclined towards certain kinds of dance, and how to reduce some of that disinclination.

Just Not Feeling It

Why do men not feel the same attraction to dance that women do? There seem to be two main reasons.

The first regards the innate sense of the body. Women seem to have a more interior sense of the body, so movement is more readily felt as something centred in one's own body. Men's sense of their bodies has a more external focus. Men are more oriented to outwardly focused action. They act to change their environment or interact with objects. Women seem drawn to dance even as a solo activity, even a kind of meditation, centred in the sensations of the body in movement. Men can do that, or learn to focus in that way, but it tends to be less spontaneous. You do not tend to see men get up and dance on their own, enjoying it for its own sake in that interior way.

The second reason men are not as drawn to dance regards the different forms of emotionality in men and women. The relevant difference here is between what could be called competitive interplay and consensual interplay. Men are more spontaneously drawn to a competitive form of interplay in bodily action and so incline more strongly to games and sports as their forms of social-bodily interaction. Women are more drawn to consensual interplay of bodily action, and dance provides the classic form of that.

The development of stylised dance involving man-woman couples meets a more evident desire of women than men. It draws women into a form of bodily activity that differentiates consensual bodily interplay, and most importantly, with men, and which lends itself perfectly to the romantic sense.

What is the attraction?

Men tend to have less sense of consensual interplay because it does not strike them as obviously containing possibilities for emotional resonance, whereas competitive interplay does. They just don't spontaneously see what the emotional possibilities of dance are. The possibilities they see in it are more to do with the opportunities for being physically close to women. We could sum up the general difference like this:

Women like the dance. The men like the women.

By contrast, women more spontaneously perceive in dance possibilities for emotional resonance. Men are often dragged along to dances by women, and the men go along with it, and enjoy it up to a point, but are often largely left unmoved by it. Women find this disappointing. They wish the men could enter into the spirit of it.

If one wishes to foster men's interest in dancing it is important to understand the underlying reasons for their lack of interest. It is important to note at the outset that men are not itching to dance, and suppressing the urge for extrinsic reasons, such as appearing 'unmanly'. In some situations that might be a partial factor, but it also reinforces the point: if it was something men spontaneously wanted to do it would already be classed as manly.

In most cases men are genuinely indifferent to dance. It does not strike an emotional chord, and so they need external motivation, typically either to keep a woman happy, or to get close to a woman in a socially approved way.

Consensual Interplay

The key to understanding men's relative indifference to dance is the notion of consensual interplay. It does not feel obvious to men how this is a form of play. Men typically love games and playfulness, they just do not recognise dance as falling into that category. Why is that?

It involves the way we pay attention to things, and the way that giving attention to something differentiates its meaningfulness. Men are drawn to competitive interplay because it centres around their desire for achievement. To win a game is a symbol of achievement so it provides the emotional measure. The unfolding of the game then differentiates the distance between the current state of play and the ultimate goal. One develops a lively sense of seeming to be getting closer or further away from the goal. This differentiates the emotional sense so that it becomes the arena for emotional interplay.

This might sound a bit abstract, so let me try to put it a bit more simply. You feel more positively if you feel you are close to winning, and less positive if you feel you are close to losing. This applies not only to the outcome of the game as a whole, but to key turning points within it. These become strong emotional markers by which you feel closer or further away from winning.

Feeling Finer Increments

Someone who has a great familiarity with a game has a highly differentiated sense of the game. He knows in fine detail what the possibilities and probabilities are that have a bearing on winning and losing. This is like having a ruler with many increments. Someone who has no familiarity with the game would be like someone trying to measure with a one metre rule divided, say, into thirds. So he has only the most rudimentary sense of the significance of what is going on. As he learns more his 'ruler' might be marked in tenths, then eventually hundredths, as he becomes more finely discriminating about the game. This is not only an abstract process. The more strongly he is invested in 'his' teams fortunes the more motivation he has to pay closer attention. Eventually his ruler might be marked in 1000ths.

This is how emotion works. The increments are the detectable fluctuations of emotion. The more important something is to you and the more closely you pay attention to it the more finely differentiated your 'emotional ruler' becomes. The more finely differentiated this becomes the greater the 'resonance' of emotion can be. We could use another metaphor. Imagine a piano with only one key per octave of pitch. The tunes you could play on it would be rather limited! Now imagine it has three keys per octave, then five, then eight. Eventually you can fill in all the main notes and play an enormous variety of music. An instrument like a guitar, or a violin has even finer increments possible, because notes can be bent, and microtones become possible. As emotion becomes more differentiated in its 'felt meaningfulness' it enables a greater resonance of emotion, a greater capacity for responsiveness to subtle signals.

For men this process of differentiation occurs more in relation to competitive interplay than consensual interplay. Their eyes might light up and they come alive at the prospect of playing or watching a competitive game because they already recognise the kind of resonance it can hold for them. For women this process of differentiation occurs more in relation to consensual interplay than it does for men. Women more commonly approach a dance with greater resonance and anticipation of its emotional possibilities. For men, anticipating a dance might only be like having a metre rule marked in thirds. They just do not perceive the relevant field of potential resonance. This is one reason women try to dress more attractively, and even sensually, for a dance because at least that evokes a kind of emotional resonance for which men have finely differentiated rulers!

Leading and Following

So how can men develop a capacity to perceive consensual interplay in dance and gain a more finely differentiated awareness of it?

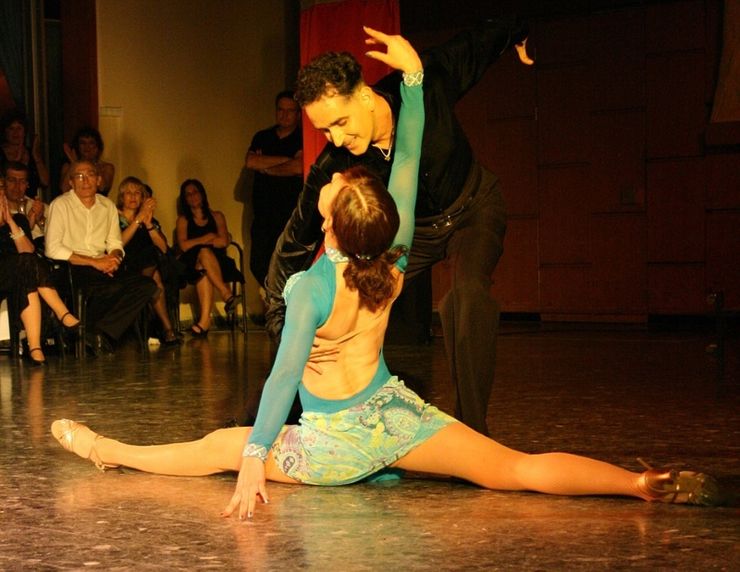

The first thing we need to do is identify the measure. If emotional perception discriminates movement towards and away from a particular measure, what is it? In competitive interplay it is the goal of winning. But in a dance the aim is not to win but to keep departing from and returning to a centre. One does not end up the victor, and the other a loser, but both remain 'in the game'. In partnered dance the two dancers move in relation to a centre that lies between them. The art lies in the ways in which they move closer and further away, and yet without breaking the artful link between them, and always resolving back to the centre. This does not make the dance static, because it is the creativity, skill and expressiveness with which they embody this two-in-one dynamic that is the point.

Although the dance begins and ends in a consensual unity, there is within it something that could be likened in some way to competition, or at least something that provides a dynamic tension that can be developed in different ways. This is the dynamic between leading and following. The customary form gives the man the role of leading and the woman of following. This is not a relation of subordination but of playfulness. Although in one sense the pivot of the dance is the centre between the dancers, in another sense the lead-man is the pivot, providing a reference point for the woman whose variations are the centrepiece of the dance as a form. So they provide two different kinds of lead or centre.

Just One Step after Another

When people are introduced to partnered dance as a social activity it is usual to teach them some set dances by getting them to memorise a series of steps. Such dances do not include improvisation but simply follow a 'script'. For men whose only experience of dance is this basic form, the meaning of 'leading' and 'following' is not likely to be apparent. If both the man and the woman memorise the steps, which are all prescribed, then in what sense is anyone leading or following? You simply wait for the music to start, and then both simply dance the set steps through till the end.

In this scenario a man is unlikely to pick up on any emotional potential in the dance as such. He might get some enjoyment from it in a social sense, and as a physical activity, and in being close to a woman, but anything else would be imperceptible. With a lot of repetition he might become quite comfortable and competent with such dancing, and yet never pick up on any other potential in it. This makes it difficult for women to get from it what they hoped because any dynamic of leading and following is rudimentary at best.

Improvisation as the Key

How much can you expect?

Some might think that you could not expect any more from simple social dancing, and that it would only be with the acquisition of greater skill that such further enjoyment would be possible. But that is not the case. In what follows I will explain a simple way to help men recognise and experience some of the emotional possibilities in dance.

Introducing Improvisation

After a short initial stage of teaching some basic prescribed dances, some improvisation is introduced. From the prescribed dances already learned you choose four short dance sequences. For example, the first might be for the partners to stand facing each other and slide four steps forward and four steps back. The second might be for the partners to turn side on to each other and step four steps forward and four steps back. In the third they stand face to face and step round in a circle four times, and in the fourth they link arms side by side and spin round four times.

Once they can do these competently without having to look at their feet or otherwise think too much, they are instructed that for the next stage of the dance they are to mix these four elements up in any order. The man is the one who has to decide which one to do next. This introduces the real notion of leading for the first time. There is an option and a decision.

A New Feeling

What effect does this have? Firstly, it gives the man a stake in the dance in a new way. He has to take on a specific responsibility, and if he falters the dance itself is affected. Men take their own competence very seriously, so straight away a man is invested more fully in the dance. At first he might find it hard to relax. But hopefully he will soon become comfortable with the mechanics of it and begin to see another possibility.

Because men have a certain propensity to competition he might realise that there is some enjoyment in not letting his partner know which option he is going to choose next. He might start trying to trick her. This means that she starts paying closer attention to him, trying to read his signals. Before long this simple dynamic can introduce a whole new feeling into the dance which is intrinsic to the form of the dance itself.

Even though this is lightly competitive the predominant dynamic is still cooperative, because their competence as a couple depends on it. The man's purpose is not to 'win' but only to add a light element of playful tension. And the woman's purpose is not to 'win' by always detecting in advance which way he is going to go, but to increase the dance's complementary nature by following as closely and seamlessly as possible.

Extending Improvisation by Stages

Once the couples are comfortable enough at this, the elements of the dance can be changed by shortening each from four counts to two. This means that decisions and responses have to be quicker, and the challenge that little bit greater.

A new stage can then be added by giving the woman some of her own improvisations as extensions of the existing movements. The dance reverts to the four count, but in the second two of each the woman is allowed to step apart from the man and make some other movement. Then he has to work out how to link seamlessly from her finishing point to one of the four starting points of the standard movements.

How might this work? With the couple-facing slide-sideways movement, the woman might use the third and fourth steps to spin around. This means that the man will have to decide whether to end up beside her or facing her for the next movement. With the arms-linked spinning-round movement the woman might decide to reverse direction after two times.

Conclusion

I won't go on any further now about the particulars of the dance, but I hope these simple examples can show how a technically simple dance can become the vehicle for men to begin learning what leading and following can add to the experience of a dance.

The key point of interest for men is that it can make the dance more playful. It becomes something in which he has to become more intentional, and in a way that evokes a more closely attentive response from the woman. Both the partners become more closely engaged, in a way that is not merely an exterior performance but which pushes them to try and 'read the other's mind'. At the same time, the artistry of the dance requires that any elements of playful rivalry have to be blended into the overall consensual form of the dance.

This approach to learning dance can be augmented by explanations of why it is done the way it is. The emotional dynamics can be explained so that the dancers gain greater clarity about what the dance can be, and how it can become more enjoyable.